Adebote Mayowa is a documentary photographer and media executive for the International Climate Change Development Initiative (ICCDI). He has spent over five years using visual storytelling to bring attention to pressing climate issues across Africa. His journey into environmental advocacy began with a transition from events photography to documentary photography, motivated by the belief that powerful imagery can shift perspectives and inspire action. Through his work, he has led and contributed to various environmental campaigns aimed at building public awareness and fostering sustainable practices.

This month, we bring you our Q&A conversations with Mayowa. We hope you find it inspiring, enjoy…

What initially inspired you to transition from event photography to environmental documentary work, and how has your perspective on storytelling evolved?

My shift from event photography to environmental documentary work was driven by a desire to create more meaningful impact with my craft. While event photography was rewarding, I often felt limited in terms of how much I could convey messages through my images.

The turning point came with the Black Oxygen Project. I witnessed firsthand how a tire “recycling” company was threatening the livelihoods of over 5,000 people in my community. The toxic emissions caused severe air pollution and health problems, yet efforts from local leaders yielded no results. Documenting this crisis, I saw not just the environmental damage, but the physical and emotional toll on the people affected. This wasn’t an abstract issue; it was our lives at stake.

Through my documentary and virtual exhibition, we attracted significant attention, sparking local and international discussions and eventually leading to concrete action—the company was shut down, and justice was restored to the community. This experience showed me the power of visual storytelling as a tool for advocacy and justice.

The success of the Black Oxygen Project was a pivotal moment that solidified my commitment to environmental work. It demonstrated that my images could do more than just capture a moment, they could drive real change.

As my journey evolved, so did my approach to storytelling. Initially, I focused heavily on aesthetics and framing the “perfect shot,” but over time, I learned to prioritize authenticity and context. Now, I aim to capture the essence of the story, focusing on the humanity behind it. My work is less about perfection and more about truth showing the struggles, resilience, and lived experiences of communities facing environmental challenges. This shift has deepened my belief in photography as a powerful tool for social change, extending far beyond mere documentation.

Could you share more about the origins and goals of the Climagraphy project? What challenges did you face, and what impact has the project had?

The origins of Climagraphy stem from my desire to bridge the gap between environmental issues and the public’s understanding through the lens of photography (CLIMAte change- photoGRAPHY). I started Climagraphy with the goal of using visual storytelling to highlight the environmental and social impacts of climate change, especially in underrepresented communities. My experience as a documentary photographer has shown me the lack of accessible, relatable narratives on these critical issues, especially from African voices. So, I envisioned Climagraphy as a platform to give these stories the visibility they deserved and to educate, inspire, and drive people toward climate action.

One of the primary goals of Climagraphy has been to create a catalog of climate realities—images and stories that showcase both the struggles and the resilience of communities facing environmental challenges. By capturing these narratives, I aim to shift perceptions about climate change from abstract (scientific)data to real, human experiences, emphasizing the urgency and personal nature of the crisis.

Like everyone one, my journey hasn’t been without its challenges. One major hurdle has been securing funding and resources, which are essential for traveling, documenting, and producing high-quality content. Additionally, gaining the trust of communities, many of whom are wary of outsiders documenting their struggles, required time, patience, and transparency. I have had to be very mindful of cultural sensitivities and make sure the communities felt their stories were represented accurately and respectfully.

Despite these challenges, we have had significant impacts with CLimagraphy. The stories shared have sparked conversations at various levels, from local community groups to international platforms. For instance, a short photo story I did on open defecation in Lagos led to government action after gaining traction online. Seeing these tangible outcomes has validated the project’s purpose and reinforced my commitment. Ultimately, Climagraphy has become more than just a collection of images; it’s a movement that strives to use the power of visual storytelling to advocate for climate action, elevate underrepresented voices, and foster a sense of environmental responsibility.

The turning point came with the Black Oxygen Project. I witnessed firsthand how a tire “recycling” company was threatening the livelihoods of over 5,000 people in my community. The toxic emissions caused severe air pollution and health problems, yet efforts from local leaders yielded no results. Documenting this crisis, I saw not just the environmental damage, but the physical and emotional toll on the people affected. This wasn’t an abstract issue; it was our lives at stake.

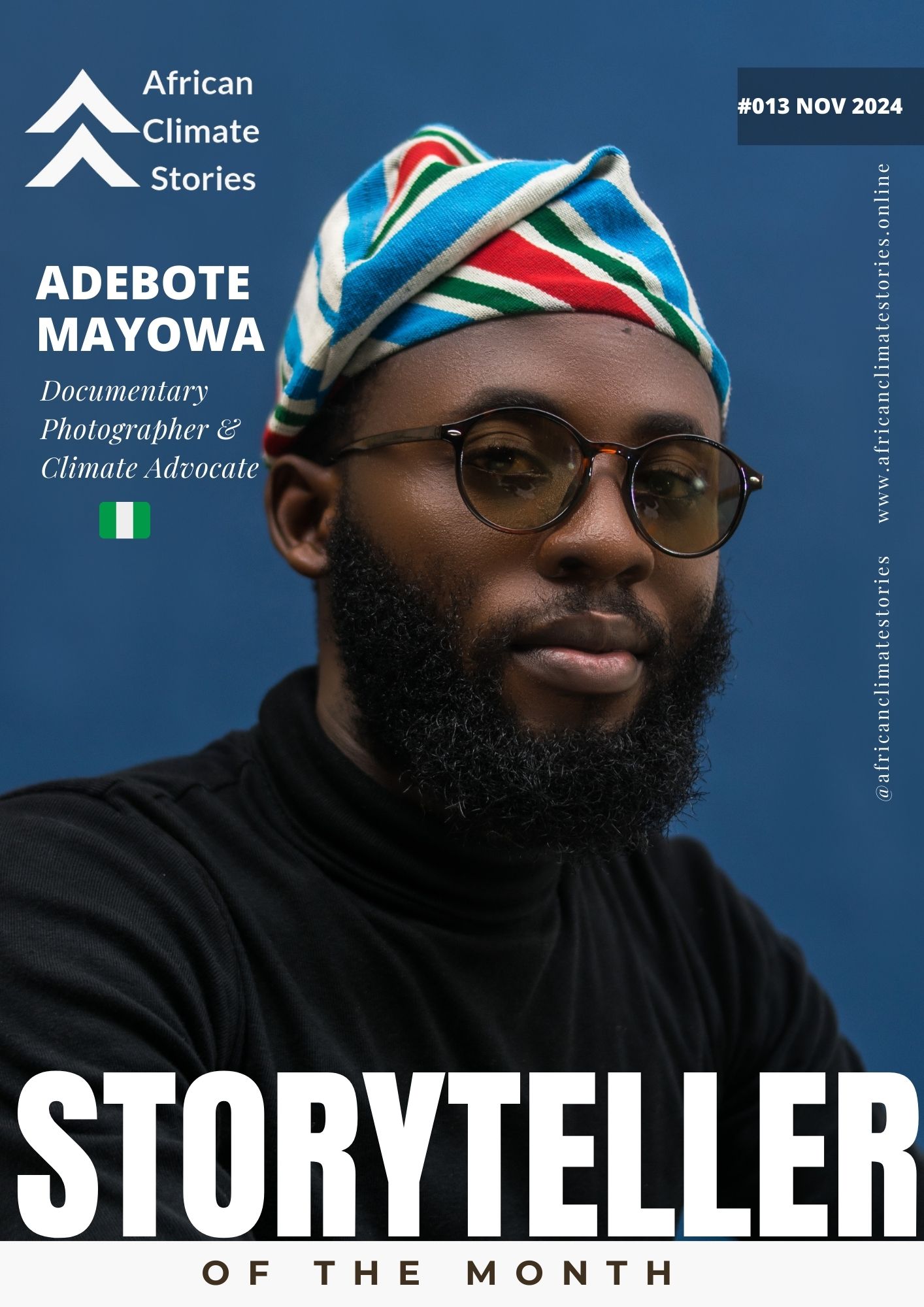

Adebote Mayowa

Documentary Photographer

You documented the experiences of a Nigerian community affected by a tire-burning facility, which led to policy changes. How did you approach this story, and what were the key elements that helped make it impactful?

The Black Oxygen project was deeply personal for me, as I grew up in this community and experienced the effects firsthand. The pollution affected everyone’s health, and it was especially distressing to see how it impacted children and the elderly. This personal connection became a key driving force behind the story, as I wanted to bring to light what my community was going through, beyond just saying.

My approach was to first build trust and engage other community members in a collaborative way. Since they knew me, it made them more willing to share their experiences openly, and I spent time documenting the toll that the tyre-burning facility (owned by a chinese) had taken on their lives. I captured not just the physical impact the blackened plant and fish pond around, the soot-covered home but also the emotional toll it had on people who felt they had no choice but to endure it.

Key elements that made the story impactful included a mix of visual and emotional storytelling. I captured detailed photos and videos of the polluted landscapes, and the people suffering from respiratory issues. I also interviewed residents who shared their frustrations, their health struggles, and their fears for the future. Combining these elements into a multimedia piece helped create a powerful narrative that humanized the issue.

The story gained traction, and once it was picked up by media outlets, it caught the attention of local authorities, who eventually pushed to address the tyre-burning menance. Reflecting on this experience, I see the power of being both an insider and an advocate. It helped me convey the urgency and depth of the issue in a way that resonated widely and, ultimately, drove action.

How have your collaborations with international organizations like the UNDP and the African Development Bank shaped your approach to climate storytelling?

Working with these organisations has given me a broader understanding of climate issues at a global level, helping me see the interconnectedness of local experiences with larger policy frameworks and international agendas. I have gained insight into the diverse ways that climate change affects different regions and communities, as well as the complexities of addressing these issues across varying cultural, economic, and political contexts.

I recall Dr Anothny Nyong (Former Director of the Climate change Department at the AFDB) encouraging me to make my storytelling more data-driven and solution-oriented. I have learned to incorporate data and research into my stories to strengthen their credibility and reach. This experience tells the importance of grounding narratives in evidence, which can make them more compelling to policymakers and stakeholders who rely on hard data for decision-making.

What insights did you gain from leading the Climate Solution Leadership Training, particularly in empowering young Africans to take climate action?

Participating in the Climate Solution Leadership Training was an eye-opening experience that deepened my understanding of both the challenges and potential of climate leadership among young Africans. Working with over 600 young participants across six Nigerian states, I noticed the immense passion and creativity that youth people bring to addressing climate issues.

One key insight for me was the importance of contextualizing climate action within local realities. Many young Africans are acutely aware of the environmental issues affecting their communities, from flooding and deforestation to pollution and waste management. But to empower them effectively, it was essential to connect these issues to their everyday lives and show them how they could make a tangible difference in their communities. Alongside the project lead, Olumide Idowu, we tailored the training to highlight locally relevant solutions, such as sustainable farming practices, community waste management, and clean energy options suited to their regions. This not only increased engagement but also inspired participants to see themselves as catalysts for localized change.

How do you approach capturing the human stories behind climate data, especially when aiming to convey complex environmental issues?

On every project I carry out,, I try to balance scientific information with the emotional depth of personal narratives and like on my project, I start by immersing myself in the community or story I’m documenting, taking time to understand the personal and cultural dynamics at play. While doing this, I try building trust and establishing a genuine connection with people, Empathy guides me to ask questions that reveal not just what people experience, but also how they feel, what they fear, and what they hope for, this elements that make the data come alive.

I look for universal themes such as health, safety, family, and livelihood that resonate with audiences globally. These themes help bridge cultural gaps and allow people from different backgrounds to empathize with those facing environmental hardships.

What are some underrepresented narratives or climate stories in Africa that you feel need more global attention, and how do you plan to bring them to light?

In Africa, desertification is rapidly affecting agriculture and displacing communities that depend on the land for survival. Yet, these communities are developing unique adaptive techniques. Stories like this are worth highlighting to showcase both the harsh reality of land degradation and the resilience of the people affected, framing their adaptive methods as models for other regions.

In Nigeria, Coastal Erosion and the Threat to Fisheries is another underrepresented narrative. People face severe erosion that threatens their homes and traditional fishing practices not forgetting to mention the overfishing and unregulated practices by international vessels depleting fish stocks, leading to both economic hardship and food insecurity. I plan to document the voices of these fisherfolk, exploring how they navigate these intersecting challenges and how local and international policies could offer solutions.

Lastly, Women in Africa are disproportionately affected by climate change, particularly in rural areas where they bear the brunt of water scarcity, crop failures, and the need to care for family members. Yet, these women are also central to sustainable farming, conservation, and grassroots climate action. By telling their stories, I want to bring global attention to the gendered impact of climate change and amplify the voices of female climate leaders, framing them as crucial allies in the fight for a sustainable future.

I plan to leverage Climagraphy as a platform for sharing in-depth photo essays and multimedia projects that combine visuals, interviews, and data. I’m currently in some conversations with CJID and hoping to workout some collaborations with journalists in their cycle to further extend the reach of these stories, ensuring they reach decision-makers and activists alike. I also want to explore immersive storytelling formats like virtual exhibitions and augmented reality to engage audiences in a more personal, impactful way.

Looking ahead, what projects or goals are you most excited to pursue in your environmental advocacy work?

One of my primary focuses is expanding Climagraphy into a larger platform that not only documents climate realities but also educates, collaborates, and fosters community action across Africa. I envision Climagraphy as a hub for African climate stories, where local communities can share their experiences and solutions, and young photographers and storytellers can learn how to amplify these voices in meaningful ways. Building this platform will require partnerships and resources, but I’m passionate about creating a space where underrepresented voices can drive global conversations on climate change.

I’m also excited about the upcoming exhibition at COP29, which aims to showcase the often-overlooked climate struggles in Lagos and across Nigeria. This exhibition will be an opportunity to reach a global audience, and I hope it serves as both a wake-up call and an invitation to action. My goal is to expand this into a traveling exhibition, bringing climate stories from various African cities to international platforms, raising awareness, and rallying support for affected communities.

Any advice to emerging climate storytellers?

Use Storytelling to Highlight Solutions, Not Just Problems Showing the challenges is vital, but balancing that with local solutions, resilience, and adaptive strategies makes your stories more hopeful and inspiring. People are more likely to engage and take action when they see solutions as well as issues.

Secondly, Storytelling can be a lonely journey, so connect with other climate storytellers, photographers, or advocates who share your vision. Whether it’s through local organizations, workshops, or online platforms, these connections will help you learn, collaborate, and stay motivated.

The journey is challenging but incredibly rewarding. Your work can bring untold stories to life, give a voice to marginalized communities, and inspire change. Keep learning, stay compassionate, and believe in the power of your lens to shape a more sustainable world.

Did you enjoy this piece? Nominate an African Artists using their skills and talents for environmental good here to be African Climate Storyteller of the Month